When the AML juggernaut diverted onto a side-road

As the global standard-setter, some might accuse the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) for the epic “effectiveness” fail of the modern anti-money laundering experiment – specifically, the absence of any material, demonstrable, verifiable, impact on serious profit-motivated crime.

It is easy to blame FATF.

It would also be wrong.

Monumental failure on a global scale spanning three decades requires great stoicism in the face of countervailing evidence by many collaborators, sponsors, and enablers.

Moreover, the blame game is seldom productive.

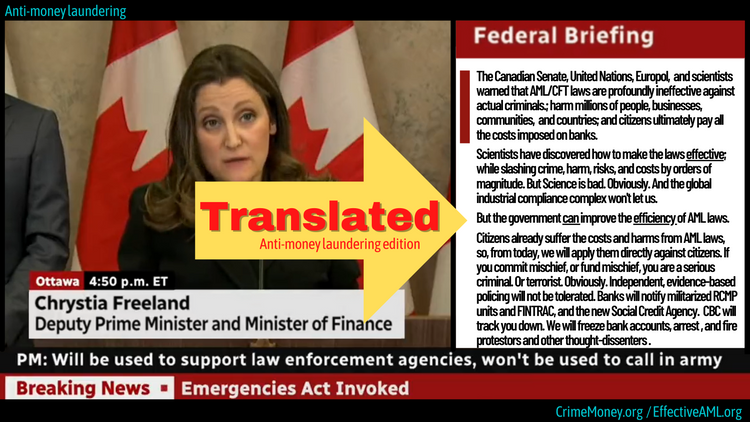

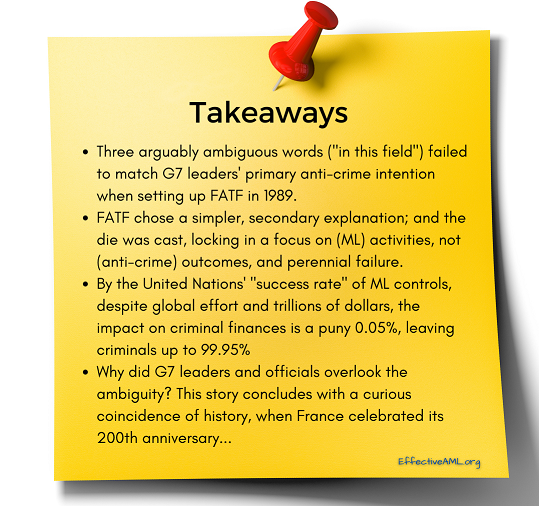

Sometimes, however, there may be constructive exceptions. If power elites share some responsibility for the great anti-money laundering experiment veering from its intended path (the latest account of the United Nations' “success rate” of ML controls is a puny 0.05% - leaving criminals up to 99.95%), national leaders might decide to plant a fresh road sign and reprogram the GPS to redirect the juggernaut towards effectiveness, as they originally intended.

By way of background to the curious incident in AML history related in this story, rather than the usual online diploma – which can only inculcate a narrative and teach skills for operating “in” any system – I completed a PhD, framed in policy effectiveness and outcomes, to explore the system’s foundational underpinnings – including when, where, how, and why the modern anti-money laundering movement diverted from its original goal.

I have also nearly concluded the next phase, uncovering new ways enabling the juggernaut to revert to its primary course. However, with the industry stoically ignoring the real problem (at least, according to evidence of the past 32 years, as outlined here), and straight-out refusing to engage in any debate about the effectiveness of its standards (as here [fifth to last paragraph]), the chance of spontaneous epiphany for effectiveness seems slim.

More constructively than repeatedly bashing one's head against the proverbial brick wall, I am therefore now mostly focused on practical new ways to allow any country or national law enforcement agency, or bank, to quietly act as a leading catalyst, triggering a substantial, demonstrable reduction in crime – while slashing regulatory risks and compliance costs by an order of magnitude – risk free. (Countries and banks respectively can keep the “FATF tick” and regulator's approval; indeed, improve both). The latest research indicates that it no longer needs to be a zero-sum game.

In the meantime, this is a brief story from the first phase of research, about a peculiar fork in history which suggests that FATFs abrupt course change may not be its fault alone. G7 leaders and officials – and a curious series of incidents involving fast planes, US college students, champagne, and a dancing bear – may have had something to do with it.

First, let me set the scene and introduce the main protagonists.